Μια μικρής κλίμακας ανασκαφική έρευνα που διεξήχθη το 2000 στην περιοχή Βασιλίτσι, στην νότια Μεσσηνία, αποκάλυψε τα απομεινάρια μιάς μέχρι τότε άγνωστης τρίκλιτης εκκλησίας του 13ου αιώνα με μια σειρά από ταφές κατά μήκος του βόρειου τοίχου της.

Τα αρχιτεκτονικά κατάλοιπα, μαζί με τά σκελετικά, νομισματικά, και κεραμικά ευρήματα, μας επιτρέπουν να σχηματίσουμε μια εικόνα από την καθημερινή ζωή μιας μικρής αγροτικής κοινότητας του μεσαίωνα.[1][2]

Τα ερείπια της εκκλησίας βρίσκονταν μισοθαμμένα σε μια πλαγιά ανάμεσα στο σύγχρονο χωριό Βασιλίτσι και την περιοχή που είναι γνωστή ως Σέλιτσα, στο νότιο άκρο της Μεσσηνίας, στο ακρωτήριο του Ακρίτα[3] (Εικ.1).

Ο αρχαιολογικός χώρος αν και ορατός τμηματικά έχει αγνοηθεί μέχρι τό 2000[4]. Η εκκλησία είναι χτισμένη σε μια απότομη πλαγιά, σε άξονα ανατολής- δύσης. Περισσότερο από το ήμισυ της δομής είχε καταρρεύσει και θαφτεί.

Όταν απομακρύνθηκε η επιφανειακή βλάστηση, έγινε φανερό ότι η προς τα κάτω μετατόπιση της γης είχε δημιουργήσει αντίστοιχη καθίζηση του μνημείου με την νότια πλευρά του ναού να παραμένει πάνω από το έδαφος, ενώ οι βόρειες και ανατολικές πλευρές ήταν εντελώς θαμμένες (Εικ.2 και κατόψεις εικ. 3-4).

Υπήρχε επιτακτική ανάγκη για την αντιμετώπιση της αστάθειας που παρατηρήθηκε σε πολλά τμήματα της τοιχοποιίας.

Ως εκ τούτου, αποφασίστηκε ότι μια περιορισμένη ανασκαφή θα έπρεπε να διεξαχθεί προκειμένου να αποκαλύψει το βόρειο τμήμα για να ολοκληρωθεί η σχεδιαστική αποτύπωση του μνημείου, ενώ άμεση ήταν η ανάγκη να ληφθούν μέτρα για την εδραίωση της τοιχοποιίας.

Η ανασκαφή

Συνολικά έξι τομές ανασκάθηκαν στη βόρεια και ανατολική πλευρά του ναού[5] (Εικ.5-6).

Σε όλες τις τομές, κάτω από το επιφανειακό στρώμα του χώματος, βρέθηκα μεγάλες ποσότητες από πέτρες που είχαν πέσει από τα ανώτερα επίπεδα του κτιρίου, καθώς και σπασμένα κεραμίδια από τη στέγη. Μερικοί λίθοι έφεραν ίχνη του ασβεστοκονιάματος που χρησιμοποιήθηκε στην κατασκευή του τοίχου. Συλλέχθηκαν επίσης πολλά θραύσματα από ζωγραφισμένα κονιάματα που κάποτε επικάλυπταν το εσωτερικό του κτηρίου.

Η απουσία ίχνους φωτιάς όπως απανθρακωμένα ξύλα ή κάρβουνα δηλώνουν ότι πιθανόν το μνημείο είχε καταρρεύσει από φυσικά αίτια όπως διάβρωση του εδάφους ή σεισμό ή και κατολίσθηση.

Το στρώμα θεμελίωσης του ναού ανασκάφηκε ακριβώς πάνω στο μαλακό φυσικό βράχο. Τμήματα του αρχικού δαπέδου του κτιρίου βρέθηκαν σε δύο τάφρους (Α και Β). Η ανασκαφή εκπλήρωσε τον στόχο της αποκαλύπτοντας όλη τη βόρεια πλευρά του ναού. Στην ανατολική πλευρά αποκαλύφθηκαν τα υπολείμματα τριών αψίδων του ιερού. (Εικ.3).

Η χρονική περίοδος κατασκευής του ναού προσδιορίσθηκε από τα μικρο-ευρήματα και την κεραμική. Η ανευρεθείσα κεραμική από τις ταφές που αποκαλύφθηκαν στον βόρειο τοίχο του ναού, χρονολογούνται στο δεύτερο μισό του 13ου αιώνα. Μεταγενέστερη κεραμεική του 18ου και 19ου αιώνα που βρέθηκαν σε διάφορα σημεία καταδεικνύουν την χρήση του μνημείου και μετά την μερική κατάρρευσή του.

Τομή Α

Η τομή Α περιλάμβανε ένα μεγάλο τμήμα της ανατολικής πλευράς του ναού, συμπεριλαμβανομένου και του ιερού, με συνολικές διαστάσεις 3,50x 2,60μ. Βρέθηκαν τείχη της κεντρικής αψίδας με τμήματα του αρχικού σοβά, με ίχνη χρώματος.

Μέρος του αρχικού δάπεδο του ναού αποκαλύφθηκε κατασκευασμένο από ένα μίγμα κονιάματος και χώματος με υπόστρωμα από μικρές πέτρες και σπασμένα κεραμίδια. Αποκαλύφθηκε το τείχος που στήριζε την κεντρική αψίδα του ιερού σε ύψος περίπου 3,50μ. Το τείχος χτίστηκε με εναλλασσόμενες σειρές από τούβλα και πέτρες (Εικ.3).

Στην τομή αυτή βρέθηκαν τμήματα κεραμεικής. Όσα βρέθηκαν στα χαμηλότερα στρώματα χρονολογούται στα μέσα του 13ου -έως τα μέσα του 14ου αιώνα (Εικ.16), ενώ εκείνα που βρέθηκαν κοντά στα επιφανειακά στρώματα αποδίδονται στον 18ο- 19ο αιώνα (Εικ.15,18,20). Επίσης βρέθηκαν πολλά θραύσματα από γυαλί τα οποία δεν μπορούν να χρονολογηθούν με ακρίβεια.

Τομή Β

Η τομή Β έγινε στο βορειοδυτικό τμήμα του κυρίως ναού, στο σημείο της σύνδεσης του με τον νάρθηκα. Το τμήμα του βόρειου τοίχου του κτιρίου αποκαλύφθηκε σε μήκος κατά μήκος του ορύγματος. Στον τείχο υπήρχαν τμήματα του σοβά. Η επιφάνεια του σοβά ήταν καφετί- κίτρινο, αλλά αρχικά πρέπει να ήταν λευκό.

Η ανασκαφή της ανατολικής πλευράς αποκάλυψε ίχνη φωτιάς, μικρών διαστάσεων, περίπου 0,45x 0,60μ., σε βάθος περίπου 2,05μ. έως 2,18μ. Δεν παρατηρήθηκαν ιχνη φωτιάς σε οποιοδήποτε άλλο μέρος του κτιρίου, έτσι αυτό θα πρέπει να θεωρηθεί ως μεμονωμένο περιστατικό και όχι ως ένδειξη μιας πυρκαγιάς που θα μπορεί να είχε καταστρέψει την εκκλησία.

Στη βορειοδυτική γωνία του ναού μεταξύ του βόρειου τοίχου και του εγκάρσιου τοίχου, η ανασκαφή αποκάλυψε ταφή ενός παιδιού εντός κιβωτιόσχημου τάφου με πέτρινη πλαϊνή επένδυση και πλάκες που κάλυπταν τον τάφο (ταφή 2).(Εικ.8) [6]

Ο τάφος, με εξωτερικές διαστάσεις 0,90x 0,43μ., ήταν παράλληλος και σχεδόν σε επαφή με τον βόρειο τοίχο. Η ανασκαφική έρευνα στην περιοχή έξω από το βόρειο τοίχο σε βάθος 3,07μ., αποκάλυψε την ταφή δύο ενήλικων θαμμένων κατά μήκος του βόρειου τοίχου με το κεφάλι να δείχνει προς τα δυτικά και να υποστηρίζετε από δύο πλάκες που είχαν τοποθετηθεί κάθετα στο έδαφος σε μια ορθή γωνία μεταξύ τους. (ταφή 1 και 4) (Εικ.9) [7]

Τομή Γ

Η τομή Γ περιλάμβανε την περιοχή έξω από το βόρειο τοίχο του νάρθηκα.

Ο αρχικός στόχος της ανασκαφικής έρευνας ήταν να ανακτήσει το μέρος του ναού που αποτελεί τη συνέχεια του βόρειου τοίχους του νάρθηκας. Αυτό θα μας βοηθήσει να εξακριβώσει την ακολουθία των πιθανών οικοδομικών φάσεων.

Σε βάθος 2,30 m, βρέθηκε ένας μικρός θησαυρός από έξι Ενετικά νομίσματα, περ 2.10μ. από τη βορειοδυτική γωνία του μνημείου και 0,60μ. από την εξωτερική πλευρά του νάρθηκα(εικ.14). Ο θησαυρός ήταν πιθανότατα κρυμμένος στο πάνω μέρος των τοίχων του ναού, και έπεσε στο έδαφος, όταν η εκκλησία κατεδαφίστηκε. (Εικ.11)

Η ανασκαφή αποκάλυψε το κατώφλι της πύλης του νάρθηκα στο βόρειο τοίχο. (Εικ.10). Το κατώφλι, που ήταν κατασκευασμένο από μία μεγάλη πέτρα, βρέθηκε σε βάθος περίπου 2μ. Μια σειρά από πλάκες βρέθηκε έξω από την πόρτα, σε την επαφή με το βόρειο τοίχο του νάρθηκα. Αυτά είτε ανήκαν σε πεζοδρόμιο ή σχημάτιζαν σκαλιά που οδήγησαν στην πόρτα.

Τομή Δ

Η τομή Δ έγινε έξω από το βόρειο τοίχο, ανάμεσα στις τομές Α και Β, προκειμένου να αποκαλύψει το υπόλοιπο τμήμα του βόρειου τοίχου, τμήμα του οποίου αποκάλυψε η τομή Β. Ήταν ένα ορθογώνιο όρυγμα διαστάσεων 1,90x 1,30μ. Η ανασκαφή ξεκίνησε σε βάθος περίπου 2,50μ. Αμέσως μετά την αφαίρεση του επιφανειακού στρώματος, τα ίχνη του βόρειου τοίχου ήταν εμφανή σε όλη την τομή.

Σε βάθος 3μ., η ανασκαφή αποκάλυψε ένα μεγάλο αριθμό οστών που ανήκαν σε πολλές ταφές, εκ των οποίων μόνο δύο ήταν αδιατάρακτες (ταφές 1 και 3), (Εικ.11).

Οι ταφές πιθανότατα καταλάμβαναν μια ευρύτερη περιοχή έξω από την βόρεια πλευρά του ναού, πολύ πέρα από τα όρια των τομών.

Η εργασία στην τομή Δ αποκάλυψε την ταφή 1 (Εικ.12). Ο σκελετός τοποθετήθηκε σε μία εκτεταμένη στάση με τα χέρια σταυρωμένα πάνω στο στήθος. Γύρω από τα χέρια του ατόμου ήταν όστρακα από αγγεία καθημερινής χρήσης (Εικ.19).

Επιπλέον, ένα κρανίο και μερικά οστά -κατά πάσα πιθανότητα προέρχονταν από παλαιότερη ταφή- είχαν τοποθετηθεί στα πόδια του σκελετού. Η τοποθέτηση αυτών των οστών δεν ήταν τυχαία, αλλά συνειδητή πράξη από τους ανθρώπους που εκτέλεσαν την ταφή 1.

Ανατολικά της ταφής 1, βρέθηκε μια άλλη παρόμοια αδιατάρακτη ταφή, επίσης, παράλληλα με το βόρειο τοίχο (ταφή 3) (εικ.13).[8]

Οι ταφές 1 και 3 παρουσιάζονται πολλές ομοιότητες. Και οι δύο σκελετοί είναι σε εκτεταμένη στάση, με το κεφάλι στηριγμένο με πέτρες και με κατεύθυνση προς τα δυτικά. Τα άνω τμήματα των βραχιόνων είχαν τοποθετηθεί παράλληλα προς το σώμα, ενώ τα χέρια διασταυρώνονται πάνω από το στήθος. Δύο πέτρες κάθετες προς το έδαφος υποστήριζαν το κεφάλι σε όρθια θέση. Οι δύο ταφές πρέπει να ανήκουν στην ίδια χρονική περίοδο.

Κεραμικά ευρήματα που συνδέονται με τις ταφές περιλαμβάνουν όστρακα τύπου proto-majolica και ένα σχεδόν άθικτο υστεροβυζαντινό εγχάρακτο γυάλινο μπολ διακοσμημένο με ομόκεντρους κύκλους (Εικ.17).

Τομή Ε

Η τομή Ε αποκάλυψε την υπόλοιπη τοιχοδομία στην βορειοανατολική και βορειοδυτική πλευρά του ναού, χωρίς να βρεθούν κεραμικά ή άλλα ευρήματα.

Τομή ΣΤ

Η τομή ΣΤ (2,40x 1,30μ.) έγινε στην περιοχή έξω από την κεντρική και νότια αψίδα της εκκλησίας.

Ένα από τα κεραμίδια της σκεπής βρέθηκε σχεδόν ανέπαφο (Εικ.21). Η τριπλή αψίδα του διακονικού αποκαλύφθηκε τέλεια διατηρημένο, με το παράθυρο κατασκευασμένο από κάθετες πλάκες.

Η τομή ΣΤ απέδωσε λίγα ευρήματα όπως το τμήμα μιάς μεγάλης μαρμάρινης βάσης (Εικ.22), που πιθανώς να ήταν τμήμα της τράπεζας του ιερού.

Η χρονολόγηση του ναού

Η χρονολόγηση του ναού στο Βασιλίτσι (εικ.23) καθορίζεται κυρίως από το ανασκαφικά ευρήματα. Τα πρώτα διαγνωστικά κεραμικά, τα οποία προέρχονται κυρίως από τις ταφές, χρονολογούνται με βάση παράλληλων κεραμικών ευρημάτων από άλλες περιοχές της Ελλάδας, όπως η Κόρινθος,[10] και μπορούν να αποδοθούν στα μέσα ή στο δεύτερο μισό του 13ου αιώνα.

Δεδομένου ότι οι ταφές είχαν τοποθετηθεί δίπλα στα θεμέλια του κτιρίου, είναι λογικό να χρονολογήσουμε την ανέγερση της εκκλησίας στο πρώτο μισό του 13ου αιώνα. Όλα τα αγγεία κάτω από το στρώμα καταστροφής χρονολογούνται στον 13ο- 14ο αιώνα.

Ο μικρός θησαυρός νομισμάτων από τα τέλη του 14ου αιώνα, που βρέθηκαν στην τομή Γ, σημάδι ανασφάλειας ή επικείμενου κινδύνου, δείχνει ότι το κτίριο ήταν ακόμα όρθιο και λειτουργούσε εκείνη τη στιγμή.

Η παρουσία της εστίας φωτιάς στο κεντρικό τμήμα του ναού μπορεί να υποδεικνύει ότι μετά από ένα ορισμένο σημείο η εκκλησία είχε χρησιμοποιηθεί σποραδικά, με την εστία να εξυπηρετεί τις ανάγκες μαγειρέματος ή θέρμανσης ενός περαστικού.

Σε κάθε περίπτωση, η περίοδος χρήσης του ναού μπορεί να τοποθετηθεί με ασφάλεια από τα μέσα του 13ου έως τα τέλη του 14ου αιώνα. Η ύπαρξη κεραμικής του 18ου και του 19ου αιώνα πάνω από το στρώμα καταστροφής ίσως συνδέεται με την δραστηριότητα στην περιοχή, πιθανότατα μετά την κατάρρευση της οροφής. Δεν μπορεί να προσδιορίσει με βεβαιότητα πότε κατέρρευσε η στέγη, αλλά πιθανόν να συνέβη κάποια στιγμή στον 18ο αιώνα.[11-23]

Βασιλίτσι: Ιστορία και τοπογραφία

Για να απαντήσει κανείς σε ερωτήσεις σχετικά με τους οικοδόμους της εκκλησίας στο Βασιλίτσι ή την ταυτότητα εκείνων που θάφτηκαν σε αυτήν, θα πρέπει να εξεταστεί η τοπογραφία και η κατοίκηση στην περιοχή, που δεν έχουν αλλάξει και πολύ από τους μεσαιωνικούς χρόνους.

Δυστυχώς, τα ιστορικά αρχεία για τον 13ο έως τον 15ο αιώνα είναι σχεδόν ανύπαρκτα και δεν υπάρχουν γραπτές πηγές ή αναφορές για την περιοχή. Επιπλέον, αρχαιολογικά και αρχιτεκτονικά στοιχεία για την κατοίκηση της ευρύτερης περιοχής του Βασιλιτσίου κατά τη διάρκεια της ίδιας περιόδου, από επιφανειακές έρευνες, είναι ελάχιστα.

Επειδή δεν μπορούμε να προσδιορίσουμε το όνομα του ναού και της τοποθεσίας με βάση κείμενα των Βυζαντινών, Φράγκων, ή Ενετών (μέχρι το 1500), χρησιμοποιείται το όνομα της πλησιέστερης σύγχρονης κοινότητας, Βασιλίτσι, για η εκκλησία και το τοπικό τοπωνύμιο Σέλιτσα για την ευρύτερη γεωγραφική θέση του μνημείου.

Η παλαιότερη αναφορά του χωριού Βασιλίτσι είναι στην απογραφή του Grimani το 1700, όπου καταγράφεται πως κατοικείται από επτά οικογένειες, με 14 άνδρες και 10 γυναίκες.

Στα βυζαντινά και μεσαιωνικά χρόνια η περιοχή παρέμεινε στη σκιά της γειτονικής Κορώνης και θεωρείται ότι ακολούθησε την ίδια μ΄αυτήν τύχη. Ωστόσο, ακόμη και για Κορώνη, οι πληροφορίες για την περίοδο από τον 7ο έως το τέλος του 12ου αιώνα, είναι εξαιρετικά φτωχές. Το μόνο μνημείο αυτής της εποχής που παραμένει στην Κορώνη είναι μια ερειπωμένη βασιλική που βρίσκεται μέσα στο κάστρο και πιθανότατα χρονολογείται από τον 7ο- 8ο αιώνα.

Οι ιστορικές αναφορές για την περίοδο πριν από το 1204 περιορίζονται στην απλή αναφορά του βυζαντινού κάστρου της Κορώνης που εύκολα καταλαμβάνεται από τους Φράγκους το 1205. Στον ύστερο Μεσαίωνα (13ος- 15ος αιώνας), η Κορώνη έγινε η μεγάλη και γνωστή αποικία των Ενετών (Coron/ Corone). Ωστόσο, τα όρια της βενετικής ελεγχόμενης περιοχής, και μαζί της η μοίρα της περιοχής του Βασιλιτσίου, δεν καθορίζονται με σαφήνεια. Οι ιστορικοί πιστεύουν ότι στους δύο αιώνες της Ενετοκρατίας, οι Βενετοί κατείχαν μόνο την Κορώνη και την άμεση περιοχή της. Αν και τα εδάφη που κατείχαν οι Βενετοί και οι Φράγκοι δεν είναι γνωστά με ακρίβεια, το μόνο σίγουρο είναι ότι στην αρχή του 15ου αιώνα, οι Βενετοί είχαν καταλάβει την περιοχή μεταξύ Κορώνης και Μεθώνης (συμπεριλαμβανομένου φυσικά και του Βασιλιτσίου), και οχυρώνονται απέναντι στην επερχόμενη οθωμανική απειλή.

Η ανασκαφείσα εκκλησία βρίσκεται σήμερα απομονωμένη σε μια γεωργική έκταση φυτεμένη κυρίως με ελαιόδεντρα. Η κοντινότερη σύγχρονη κοινότητα, το χωριό Βασιλίτσι, βρίσκεται σε απόσταση άνω των 10 χιλιομέτρων. Κατά την πορεία στους σύγχρονους δρόμους που οδηγούν από το Βασιλίτσι στην Σέλιτσα, κατά διαστήματα συναντάμε απομονωμένα, εγκαταλελειμμένα και ερειπωμένα σπίτια, ανάμεσα στα ελαιόδεντρα, όπως τα ερείπια των δύο μικρών σπιτιών περίπου 200μ. βορειοανατολικά της ανασκαφής (Εικ.25).

Και τα δύο είναι μονόχωρα, πετρόκτιστα με κατεστραμένες ξυλόστεγες, και δυστυχώς δεν προσφέρουν καμία ένδειξη ως προς τη χρονολογία τους. Ανήκουν στο κοινό είδος των ελληνικών αγροτικών γνωστών ως μονόσπιτα, και πιθανώς χρησιμοποιήθηκαν από τις οικογένειες των αγροτών ή βοσκών που εργάζονταν στις γύρω περιοχές. Η χρήση της πέτρας και όχι πλίνθων μπορεί να υποδεικνύει ότι αυτές ήταν μόνιμες εγκαταστάσεις, και όχι προσωρινές κατασκευές για την περίοδο της συγκομιδής. Οι αγρότες δεν χρειάζεται πλέον να ζήσουν στην περιοχή αφού τα σύγχρονα μέσα μεταφοράς τους επιτρέπει να φτάνουν εύκολα τα εδάφη τους από το χωριό Βασιλίτσι.

Κοντά σε αυτά τα σπίτια βρίσκεται ένα άλλο μικρό εκκλησάκι, αφιερωμένο στον Άγιο Ιωάννη (Εικ.26). Η εκκλησία έχει ένα ενιαίο διάδρομο, ξύλινη οροφή, και προθάλαμο στη βόρεια πλευρά. Είναι το μόνο κτίριο από τα τρία που είναι σήμερα σε χρήση. Στην εκκλησία αυτή έχουν γίνει πρόσφατες επισκευές και βελτιώσεις (νέα κεραμίδια και γύψο τοίχο). Ωστόσο, ορισμένα στοιχεία - όπως η μορφή των τριών ημικυκλικών αψίδων που προεξέχουν στην ανατολική πλευρά- δείχνουν ότι αυτή δεν μπορεί να είναι μια σύγχρονη κατασκευή, αλλά μάλλον ένα παλαιότερο κτίριο (ίσως της πρώιμης σύγχρονης περιόδου) που εξυπηρετεί ακόμα σποραδικά τοπικές θρησκευτικές ανάγκες. Είναι επίσης ενδιαφέρον να σημειωθεί ότι η εσωτερική διαρρύθμιση των αψίδων Αγίου Ιωάννη, με τα ημικυκλικά τόξα τους και ενσωματωμένα ράφια, μοιάζει πολύ με τη δομή της ανασκαφείσας εκκλησίας. Κάποιος θα μπορούσε μάλιστα να υποθέσει ότι η εκκλησία του Αγίου Ιωάννη είναι ο πρώιμος σύγχρονος διάδοχος του ναού του 13ου αιώνα, το οποίο λόγω των κατολισθήσεων κατέστει επικίνδυνος και ασταθής.

Τα ερείπια ενός μικρού εγκαταλειμμένου οικισμού βρίσκεται περίπου 1,5 χιλιόμετρο ανατολικά της περιοχής (Εικ.27) και πρέπει να ταυτίζεται με την ονομασία Σέλιτσα, ένα όνομα που χρησιμοποιείται σήμερα για να ορίσει τη γύρω περιοχή. Αποτελείται από περίπου 20 μικρά σπίτια του μονόχωρου τύπου που αναφέρθηκε παραπάνω. Τα περισσότεροι από αυτά έχουν στέγες που έχουν καταρρεύσει, με τους γύρω τοίχους να στέκουν ακόμα. Σε κάθε περίπτωση, αυτό το χωριό φαίνεται να ήταν το κέντρο της ευρύτερης περιοχής σε παλαιότερη περιόδο, αλλά δεν υπάρχουν στοιχεία για ακριβή χρονολόγηση.

Το μοτίβο κατοίκησης για την περιοχή αυτή, περιλαμβάνει μεγάλες συγκεντρώσεις σπιτιών (Βασιλίτσι ή Σέλιτσα) μαζί με ομάδες απομονωμένων κατοικιών στην ύπαιθρο. Οι κατοικίες αυτές εξυπηρετούσαν τις γεωργικές δραστηριότητες των κατοίκων και πιθανόν να χρησιμοποιούνταν όλο το χρόνο. Η ανασκαφήσα εκκλησία, καθώς και το μετέπειτα θρησκευτικό κτίριο στην ίδια περιοχή (Άγιος Ιωάννης εικ.26), χτίστηκαν για να εξυπηρετήσουν τις ανάγκες των κατοίκων μιας απομονωμένης ομάδας σπιτιών - ίσως ακόμη και μιας μεγάλης οικογένειας. Αυτό το είδος της περιφερειακής κατοίκησης έχει εντοπιστεί και αλλού στη Μεσσηνία, όπως για παράδειγμα στην περιοχή του Νιχωρίων.

Τα Νιχώρια στην μεσοβυζαντινή εποχή θεωρείται ότι έχει κατοικηθεί από τα μέλη μιας εκτεταμένης οικογένειας. Είμαστε τυχεροί να έχουμε έναν κατάλογο των κατοίκων διάφορων οικισμών του 14ου αιώνα στην Μεσσηνία (1354) -όπως το Κρεμμύδι, Γκρίζι, Cosmina, Vbulkano, και Petoni- γνωστών από την απογραφή του Nicolas Acciaiuoli

Είναι ενδιαφέρον να σημειωθεί, υπό το φως του μοτίβου κατοίκησης που περιγράφεται ανωτέρω, ότι όλοι οι κάτοικοι των χωριών αυτών ήταν Ορθόδοξοι, ανήκαν σε μια χούφτα των εκτεταμένων οικογενειών, με τη γεωργία ως βασικό τους επάγγελμα.

Αυτό το πρότυπο οικισμού (χωριά και απομονωμένες αγροτικές εγκαταστάσεις) παρέμεινε αναλλοίωτο στην Μεσσηνία μέχρι και την πρώιμη σύγχρονη περίοδο, όπως φαίνεται στην ανάλυση της Οθωμανικής κτηματογράφησης της περιοχής του Anavarin (Ναβαρίνο), που χρονολογείται στα 1716. [24-38]

Συμπεράσματα

Το πρότυπο οικισμού που περιγράφεται παραπάνω δεν μπορεί να διέφερε σημαντικά από εκείνη που υπήρχε στην ευρύτερη περιοχή του Βασιλιτστίου κατά τη διάρκεια του 13ου- 14ου, όταν και ο ανασκαφέν ναός ανεγέρθηκε.

Η περιοχή ήταν αγροτική με τους καλλιεργητές και τους βοσκούς που ζουν είτε σε μεγάλους οικισμούς (όπως το Βασιλίτσι ή την Σέλιτσα) ή σε μικρότερες ομάδες με λίγα σπίτια, στα οποία οποία ζούσαν κατά πάσα πιθανότητα μεγάλες οικογένειες.

Μια τέτοια μικρή κοινότητα φαίνεται να υπήρχε στον χώρο της εκκλησίας, και θα πρέπει να πιστωθεί με την ανέγερση του. Δεν υπάρχουν ευρήματα που να δείχνουν ότι στην εκκλησία υπήρχε κάποιο μοναστήρι, ενώ η ταφή παιδιού, καθώς και ενηλίκων ανδρών και γυναικών, αποκλείουν τέτοιο ενδεχόμενο. Η επιλογή του αρχιτεκτονικού σχεδίου της εκκλησίας που είναι γνωστό σε περιοχές όπως την Αττική και την Ήπειρο κατά την ίδια περίοδο (πρώτο μισό του 13ου αιώνα) δείχνει ότι η κοινότητα είχε τα μέσα να αναθέσει σε ένα εργαστήριο που ήταν σε στενή επαφή με τις ιδέες και τάσεις της εποχής και ήταν αρκετά ικανό να αναλάβει την κατασκευή. Ο τύπος της εκκλησίας είναι πανομοιότυπος με την εκκλησία της ίδιας εποχής στο κοντινό Πανιπέρι (Εικ.24) και δεν αποκλείεται να να είναι έργο του ίδιου εργοταξίου.

Η χρήση του ναού ως χώρος ταφής για τα μέλη της κοινότητας ήταν μια κοινή πρακτική στην υστερο-βυζαντινή περίοδο σε ολόκληρη την Βυζαντινή αυτοκρατορία. Οι τύποι ταφών που παρατηρήθηκαν -απλοί ενταφιασμοί και σχιστόλιθοι στην επένδυση των τάφων- είναι γνωστοί από άλλες ανασκαφές τοποθεσίες. Οι λεπτομέρειες των ταφών, όπως η τοποθέτηση του σώματος σε εκτεταμένη στάση, οι πέτρες που να στηρίζουν το κεφάλι, η επαναχρησιμοποίηση των τάφων με την τοποθέτηση κρανίων και οστών των παλαιότερων στα πόδια των νεότερων ταφών, η τοποθέτηση των κεραμικών (κύπελλα ή κατσαρόλες) δίπλα στους νεκρούς, και ούτω καθεξής, είναι τυποποιημένα στοιχεία των ταφικών πρακτικών της εποχής. Όλοι αυτοί οι παράγοντες εντάσσουν τους κατοίκους του Βασιλιτσίου στο γενικότερο πολιτιστικό πλαίσιο της μεσαιωνικής Ελλάδας.[39-45]

Nikos D. Kontogiannis: "Excavation of a 13th-century church near Vasilitsi, southern Messenia"

CATALOGUE OF FINDS

The excavation produced a number of ceramic items, connected either with the building itself (as the cover tile, 17) and its use (7,9,10,12-14,16) or with the burials (8,11,15). These are catalogued below, along with the hoard of torneselli (1-6)9 and the marble basin (18).[9]

COIN HOARD

1 Venetian billon tornesello

Fig. 14 Archaeological Repository of Pylos (ARP) no. Ml. Trench C (layer 1, group 1). Dim. 0.016 x 0.015 m. Obverse: cross pate. [+-ANTO']VENE[RIO-DVX-] Reverse: winged lion on its knees with the Gospel between its front paws. [+-]VEXI[LIFER-VENET]IA[M] Cf. Schlumberger 1878, pl. XVIII:9; Stahl 1985, pp.74-75, pls.1,2, nos.14-17; Papadopoli-Aldobrandini [1893-1919]199,vol.1, p.231, no.7, pl.Xfflill. Doge Antonio Venier (1382-1400).

2 Venetian billon tornesello

Fig.14 ARP no. M2. Trench C (layer 1, group 1). Dim. 0.016 x 0.015 m. Obverse: same as 1. [+-MICh]AEL-S[TEN'-]DV[X-] Reverse: same as 1. +[VEXILIFER-VENETIA]M- Cf. Stahl 1985, p. 75, pl. 2, nos. 18, 19; Papadopoli-Aldobrandini [1893-1919] 1997, vol.1, p.240, no. 7, pl. XIV:4. Doge Michele Steno (1400-1414).

3 Venetian billon tornesello

Fig.14 ARP no. M3. Trench C (layer 1, group 1). Dim. 0.016x 0.016m. Obverse: same as 1. +-ANTO'V[ENERI]O-DVX- Reverse:same as 1.+VEXI[LIF]ER-VEN[ETIA]M-For bibliography, see 1. Doge Antonio Venier (1382-1400).

4 Venetian billon tornesello

Fig.14 ARP no.M4. Trench C (layer 1, group 1). Dim. 0.015x 0.015m. Obverse: same as 1. +-[ANDR']QTAR'DVX- Reverse: same as 1. [VE]XI[LIFER-V]ENETI[AM] Cf. Stahl 1985, p.74, pl.1, nos.8-11; Papadopoli-Aldobrandini [1893-1919] 1997, vol. 1, p. 217, no.8, pl. XIL14. Doge Andrea Contarini (1368-1382); from the second part of his reign, since it reads Venetia and not Venecia on the reverse.

5 Venetian billon tornesello

Fig.14 ARP no.M5. Trench C (layer1, group1). Dim. 0.016x 0.015m. Obverse: same as 1. [+-ANTO']VENERIO[-D]VX- Reverse: same as1. [+VEXILIFER-]VENETIA[M]- For bibliography, see 1. Doge Antonio Venier (1382-1400).

6 Imitation of Venetian billon tornesello

Fig.14 ARP no. M6. Trench C (layer 1, group 1). Dim. 0.018x 0.016m. Obverse: same as 1. +ANT DVX Reverse: same as 1. ...X E Cf. Stahl 1985, p.76, pl.2, nos.26-28. Imitation tornesello in the name of Antonio Venier (1382-1400).

CERAMICS

Painted Decoration

7 Proto-majolica vessel

Fig.15 ARP no. KAI.38/A.13. Trench C (layer 1, group 1). (a) L.0.046, W.0.026, (b) L.0.040, W.0.026, (c) L.0.029, W.0.018m. Open shape, three fragments from rim and body (a-c). White clay (Munsell 10YR 8/2). On the interior, painted decoration on opaque tin glaze running across the rim: a band of blue consecutive circles (plait pattern) between groups of three manganese lines. Exterior is undecorated. An example of South Italian proto-majolica pottery. Similar 13th-century ceramics have been excavated at Corinth: CorinthXl, pp.105-107, 251, nos. 802, 805,fig.84,pl.XXXIV:b. 13th century.

8 Proto-majolica vessel

Fig.15 ARP no. KAI.39/A.17. Trench D (layer 3, group 2), D. 3.09, distance 0.95 from the north wall and 1.05 m from the eastern side of the trench. L. 0.068, W. 0.058m. Open shape, body fragment. White clay (Munsell 2.5YR 8/2). On the inside, painted decoration above opaque tin glaze: a gridiron pattern with bluish gray color, with brown X-shaped motifs in the spaces. The brown color strokes are covering part of the grid. Transparent, rather worn glaze covers the surface. Exterior undecorated. The fragment belongs to the group of gridiron proto-majolica. This ware was produced in several workshops of South Italy, and its presence is well attested at many sites in Greece: cf. Vroom 2003, pp. 167-169. Mid-13th to mid-14th century.

9 Proto-majolica vessel

Fig.16 ARP no. KAI.37/A.5. Trench A (layer 3, group 3). (a) L. 0.070, W. 0.045, (b) L. 0.060, W.0.045, (c) L.0.050, W.0.042, (d) L.0.075, W. 0.060, (e) L.0.050, W.0.025, (f) L.0.060, W. 0.050, (g) L.0.040, W.0.025m. Closed shape, seven fragments from neck and body. Fragments f and g, from the neck of the vessel, join (not shown mended in Fig. 16). Fragments a-c, also joining, belong to the body, as do the remaining two nonjoining fragments, d and e. Pinkish white clay (Munsell 7.5YR 8/4). Painted decoration on the exterior, over white slip. Around the upper part of the body, vertical green lines alternate with brown spirals. Yellowish glaze covers the exterior surface. As is clear from sherd d, the glaze did not cover the whole surface of the vessel; it was not applied to the lower part or the base, where only white slip is visible (sherd d is illustrated upside down). Although fragmentary, the vessel can be attributed to the proto-majolica ware from South Italy; see 7 above. Mid-13th to mid-14th century.

10 Ottoman marbled ware

Fig.15 ARP no. KAI.36/A.2. Trench A (layer 1, group 1). L. 0.040, W. 0.026 m. Open shape, rim fragment. Reddish yellow clay (Munsell 7.5 YR 7/8). White slip covers both sides of the sherd. Decoration with spots of red color above slip. Transparent shiny glaze. The fragment belongs to a variant of marbled ware, a distinctive pottery that imitated the veins of marble and was quite popular from the 16th-17th century onward. Its production was originally associated with the workshops of Pisa in Italy, but it was also widely imitated in the Ottoman empire. Vessels decorated with random spots of different colors on white slip seem to belong to the later production of the ware. For 18th-century examples from Athens, see Waage 1933, p. 327, fig. 20:g; Frantz 1942, p. 27, group 9, nos. 15, 16, figs. 30, 31; Vavylopoulou-Charitonidou 1982, p. 64, no. 19. From Kos: Kontogiannis 2002, pp. 219-220, nos. 27, 29, 30. 18th century.

Sgraffito Decoration

11 Late sgraffito bowl with concentric circles

Fig.17 ARP no. KAI.39/A.18. Trench D (layer 4, group 3). Diam. of rim 0.135, Diam. of base 0.060, H. 0.060m. Three fragments from base and body. The vessel has been restored and completed. It is a small globular bowl with a low ring base with a knot underneath. Clay reddish yellow (Munsell 5YR 7/6). White slip covers both sides of the vessel, including the exterior of the base. Incised decoration on the inside: a pair of concentric lines runs around the rim and the body, while a spiral occupies the center of the base. Green-yellow glaze covers the whole vessel. Both the glaze and the slip are worn on the inside but well preserved on the exterior. The bowl belongs to the category of late sgraffito pottery with concentric circles. Similar vessels have been found around the Aegean, and were originally identified as derivatives of Zeuxippus ware: see Armstrong 1992; 1993, pp. 304, 307-309, 313-314, 328-329, 332; Francois 1995, pp.91-96.They are usually dated to the middle or the second half of the 13th century, although their production continued well into the 15th century. For similar specimens from Greece, Turkey, Egypt, Cyprus, and Italy, see Nichoria III, pp. 381-382, nos. P1708, P1710, figs. 10-32, 10-34, pls. 10-12, 10-14; Francis 1995, pp. 91-96, serie Ih, pl. 13:c; Spieser 1996, p. 51; Francis 1999, pp. 110-132; Augusti and Saccardo 2002, p. 147; Kontogiannis 2002, pp. 226-227, no. 48; Gerstel et al. 2003, pp. 151, 158, no. 3, fig. 8, pp. 170, 181-183, nos. 44, 46, 47, fig. 34; Vroom 2003, pp. 164-165; 2005, pp. 110-111; Dori, Velissariou, and Michaelidis 2003, pp. 111-116, nos.1-15, pls. I, II; Bohlendorf-Arslan 2004, pp.128-129. Middle or second half of the 13th century.

12 Late sgraffito ware

Fig. 15 ARP no. KAI.38/A.12. Trench C (layer 1, group 1). L. 0.038, W. 0.030 m. Open shape, body fragment. Reddish yellow clay (Munsell 5YR 6/8). On the inside, coating of white slip and incised decoration with curved lines, part of an unknown motif. Yellow-green glaze. Exterior side undecorated. For relevant Late Byzantine examples, see Makropoulou 1995, p.18, nos. 48, 49, pl. 26; Francois 1995, pp. 90-91, serie Ig, pl. 13:a, b; Dori, Velissariou, and Michaelidis 2003, pp. 122-123, no.31, pl. IILa. 14th-15th century.

Plain Glazed

13 Open(?) vessel

Fig. 18 ARP no. KAI.36/A.1.2. Trench A (layer 1, group 1). Diam. of base 0.100, p.H. 0.068 m. Fragments: (a) L. 0.100, W. 0.050, (b) L. 0.055, W. 0.025, (c) L. 0.105, W. 0.087 m. Three joining fragments from the bottom and the body of an open shape. Light reddish brown clay (Munsell 5YR 6/4). On the inside, white slip and green glaze. Two traces of a tripod stilt. On the exterior, traces of glaze set directly on the clay. Probably a later production of the 18th-19th century, a period not yet thoroughly studied.

14 Closed(?) vessel

Fig.18 ARP no. KAI.36/A.1.1. Trench A (layer 1, group 1). Overall dim. (a-d): Diam. of base 0.098, p.H. 0.075 m. Fragments: (a) L.0.110, W. 0.070, (b) L.0.100, W. 0.055, (c) L.0.100, W.0.035, (d) L.0.070, W.0.040, (e) L.0.070, W.0.035, (f ) L.0.075, W. 0.035, (g) L.0.050, W. 0.040m. Seven fragments from bottom and body. Four of the surviving fragments (a-d) join and come from the bottom and the body of the vessel. Two (e,f) also join and come from the body. Light reddish body (Munsell 5YR 7/4). Plain glaze covers both sides. The exterior, apart from the bottom, is covered with light greenish glaze that crackles. The interior is covered with shiny brown crackled glaze. Belongs to the same category as 13. 18th-19th century.

Undecorated

15 Cooking pot

Fig.19 ARP no. KAZ.39/A.19. Trench D (layer 4, group 4). H. of vessel 0.155, W. of handle 0.045, Diam. of base 0.130, Diam. of rim 0.160 m. Based on the surviving 21 fragments, the pot was restored and completed as a cooking pot with a flat base, slightly globular body, vertical strap handle from rim to body, and curved rim. It was decided to restore the vessel with only one handle, rather than two, since no evidence of a second handle was preserved. A two-handled shape cannot be excluded, however, and remains a strong possibility. Reddish brown clay (Munsell 2.5YR 5/4) with many inclusions and mica. Signs of burning on the outside, probably from use in a hearth. No evidence of decoration or glaze. If the one-handle restoration is correct, the vessel could belong to Bakirtzis s group A2, "pots with flat base and one handle" (1989, pp.36-39, no. 6, pl. 3:6). For the two-handled shape, cf. 13th- to 14th-century material: Sanders 1993, pp. 278-279, no. 63, fig. 13 (Sparta); Vroom 2003, p. 169 (Boiotia); Gerstel et al. 2003, pp. 161, 171, 184, nos. 9, 31, 32, 53, figs. 9, 22, 37 (Panakton). For the forms of cooking pots in relation to the change of diets, see Williams 2003, p. 432. Mid-13th to mid-14th century.

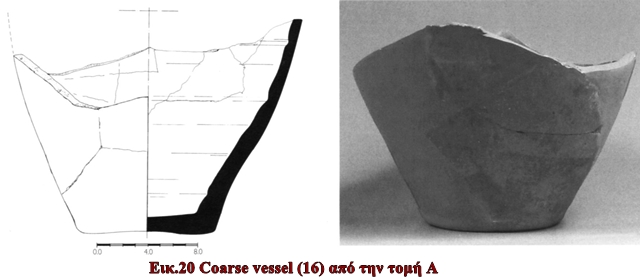

16 Coarse vessel

Fig. 20 ARP no. KAI.36/A.3.1. Trench A (layer 2, group 2). Diam. of base 0.110, p.H.0.160m. Closed shape, eight fragments, conserved and joined to form the bottom and part of the body of a closed coarse vessel. White clay (Munsell 10YR 8/2). Undecorated. This vessel must belong to the same group as 13 and 14, since it also came from the destruction layer of the church. 18th-19th century.

OTHER FINDS

17 Cover tile

Fig. 21 ARP no. KAI.39/A.21. Trench F (layer 2, group 1), D.1.75, 0.20m from the eastern wall of the church. P.L.0.310, W. 0.225, Th. 0.020- 0.030m. Large part of a roof cover tile. Clay light red-pinkish (Munsell 2.5YR 8/3). Coarse fabric, with many holes from organic inclusions. The tile is curvilinear, and its long sides spread outward. On its exterior side, circular finger marks. On the interior, traces of white mortar used for positioning on the roof, on top of the pan tiles. For cover tiles with almost identical dimensions, see Nichoria III, p.385, no. P1761-2, figs.10-81, 10-83, chapel phase 4 (Nichoria); Gerstel et al. 2003, p.163, no. 22, fig.11 (Panakton). 13th century

18 Marble basin

Fig.22 ARP no. KAI.39/L.1. Trench F (layer 5, group 4). P.H.0.250, p.W.0.155, H. of base 0.090, Th. of body 0.055m. Open shape, part of base and body. The base is slightly conical, the body externally globular and internally concave. The exterior surface is roughly worked with many small cavities, probably from the carving tools. The interior, however, which obviously served whatever use this vessel had, is very smooth and carefully worked. The basin could have been either a holy water font or a mortar. Since it was found just above bedrock at the lower layer of the trench, near the foundations of the church, it must be linked to its period of construction and use (13th-14th century). Stone holy water fonts of various sizes dating from the Byzantine era are noted in a number of churches and monasteries within Greece; see Bouras and Boura 2002, p.532. Most specimens remain unpublished, however, and it is difficult to distinguish between holy water fonts and baptismal fonts. In the few available photographs, the fonts appear in most cases to have no base; they are usually circular, globular, or octagonal, and they bear decoration with crosses, inscriptions, or floral patterns. For comparanda, see Millet 1906, pp. 459-462, fig. 3 (Mistra); Xygopoulos 1929, pp.77-79, fig.74 (Ayioi Apostoloi, Athens); Sotiriou 1935, pl. 138 (Cyprus); Orlandos 1939-1940, p.103, fig.51 (Osios Meletios, Boiotia); and Loverdou-Tsigarida 1994, pp.355-366, figs.13-15 (castle of Platamona, Thessaly). Marble mortars of the Late Byzantine or post-Byzantine period have been recorded in Thessaloniki, but their shape differs from that of 18. They have no base, and the body has four semicircular handles around the rim: see Papa- nikola-Bakirtzis 2002, pp. 358-359, nos. 420, 421. A possible ceramic mortar has been published from Panakton: Gerstel et al. 2003, p. 167, no. 28, fig.17 (14th- early 15th century). A mortar cannot be directly related to the religious function or the foundation of the church; however, it might have served the agricultural or everyday activities of the rural community that built and maintained the church. 13th-14th century.

APPENDIX- OSTEOLOGICAL REPORT

As discussed above, excavation at Vasilitsi uncovered a series of disturbed and undisturbed burials that can be dated to the 13th-14th centuries on the basis of the accompanying pottery. Disturbed burials were found in both trenches B and D, located in the area outside the church's north wall (Fig.3). Because this area was not fully excavated, apart from the narrow zone where burials 1 and 3 were discovered, observations regarding the disturbed burials, which were probably scattered around a wider space, are considered too preliminary to be included in this report. Further study will have to await future excavation of the site. The following osteological report is limited, then, to skeletal remains from the three undisturbed burials.

Burial 1

The skeleton in burial 1 (Figs. 9, 11, 12) was found in a very fragmentary condition, and the preservation of the bones is rather poor. It was consequently impossible to study the material in depth, though some conclusions were reached regarding its pathology.

Age and Sex

Based on the morphological characteristics of the pelvis,46 which was bet- ter preserved than the cranium, one can surmise that the deceased was female. According to the pubic symphyseal degeneration47 and the dental eruption and attrition,48 the individual is estimated to have been 25-30 years old at death.

Condition

The cranium is preserved in a very fragmentary state, with many parts missing. In contrast, the maxilla and mandible are well preserved, with a considerable number of teeth present. In the maxilla, the canines and the first and second premolars of the left and right side are preserved, while on the left side there is also a second incisor. The second molar on the right side is absent. In the mandible, the first and second molars of both sides are present, while the first and second premolars are observed only on the left side.

From the remaining bones, only fragments of the left and right clavicles and scapulas survive, along with 32 fragments of ribs and 43 fragments of vertebrae. The upper limbs preserve an adequate percentage of the right humerus, while the left one is completely destroyed. Only a small percentage of the left and right radius and ulna is preserved, hindering further study. The pelvis is poorly preserved, but we were able to salvage the basic parts necessary for assessment of the sex of the individual. The lower limbs, though preserved in better condition than the upper ones, are also in a fragmentary state. Finally, the right and left bone of the calcaneus and talus are present, while the metatarsals and metacarpal bones, along with their phalanges, are almost completely missing.

Observations

Despite the poor preservation of the skeletal remains, tentative observa- tions could be made about the individuals pathological condition. We were unable, however, to discover evidence concerning the cause of death. The study of the cranium fragments was of particular interest, since the left and right parietal bone, as well as the occipital bone, presented indications of thickening. According to clinical and palaeopathological research, this feature strongly indicates the presence of some sort of metabolic disease, mainly anemia.49 The poor condition of the skeleton and the absence of other cranial bones prevented the diagnosis of the exact nature of this disease. Further data were provided by the study of the teeth. The canines and premolars bore indications of enamel hypoplasia in the form of lines. This disorder in the development of teeth is still of unknown origin, yet it is usually connected to periods of stress, starvation, or certain infectious diseases.50 The examination of the vertebral column revealed that the last thoracic and lumbar vertebrae presented concavities on the body of the vertebra. These concavities, referred to as Schmorrs nodes, occur when the intervertebral disc decays, causing the nucleus pulposus to be imprinted on the body of the vertebra. The cause of this process remains undetermined, but Schmorls nodes are usually connected with serious injury or intense physical activity.51

Burial 2

Age and Sex

The skeleton in burial 2 belongs to a child of young age (Fig.8), which explains the poor preservation of the material. Based on the methods used for the assessment of adult age, the child's age was fixed between four and eight years. In this case we relied on the fusion of epiphyses and the growth of the teeth; measurements of the long bones were not taken into account for the age assessment, since the bones were in a fragmentary condition. Finally, because the skeleton belongs to a minor, the determination of sex is impossible.

Condition

In contrast to the other bones, the cranium is preserved almost complete. The maxilla and mandible are, unfortunately, fragmented, and only a deciduous molar, a deciduous incisor, and a deciduous canine were found. There were 37 fragments of ribs, yet there were no traces of the vertebral column, the clavicles, the scapula, the tibia, or the fibula. The humeri are preserved in a fair, though fragmentary, state, while the radii were almost completely destroyed. The left and right ulnae are in the same condition as the radii. Two small fragments were recovered from the pelvis, while the femurs were modestly preserved. Finally, one fragment of metatarsal was identified. Eighty small fragments were unrecognizable.

Observations

The study of this skeleton proved difficult. A large number of the bones were missing, while the existing ones had suffered multiple damage due to the burial conditions. It was impossible to determine the cause of death of this child.

Burial 3

The skeleton in burial 3 (Figs.11, 13) was found in a poor state of preservation, comparable to that of burial l.The skeleton in burial 3 is substantially more complete, but here as well the bones were recovered in a fragmentary condition, while postmortem factors seem to have affected their structure and preservation. Thus, the anthropological study could not recover sig- nificant information, apart from the age and sex of the individual.

Age and Sex

Based on the morphological characteristics of its pelvis,52 the skeleton is that of a male individual of more than 25 years of age. The pubic symphy- seal degeneration53 and the dental eruption and attrition54 were taken into consideration for the age assessment. As in the case of the skeleton in burial 1, the poor condition of this cranium made it impossible to determine the age more precisely, while the ribs added no further information.

Condition

The cranium is preserved in a fragmentary state, with a fair percentage of completeness. The maxilla and mandible also survive fragmentarily, preserving most teeth. From the maxilla the first and second molar survive on both sides. On the right side there is also the first incisor along with two premolars. On the mandible, two incisors are present, as well as the first and second premolars on both sides, and the first and second molars on the left side. A fair percentage of both clavicles is preserved, though the bones are fragmentary. The condition of the scapula and the sternum is rather poor, while the ribs survive mostly in fragments. In all, there were 121 fragments of ribs and 57 fragments of vertebra

From the upper limbs, the humeri are preserved to a fair degree of completeness, as are the right ulna and radius. The left ulna and radius had been completely destroyed. The pelvis is well enough preserved to help define the sex and age of the skeleton. Among the lower limbs, the femurs and the left tibia are wholly preserved, though in a fragmentary state. The right tibia and both fibulae, on the contrary, survive poorly. Finally, the left and right bones of the calcaneus were recovered, along with the taluses, two carpal bones, 13 metacarpals and metatarsals, and four phalanges. A total of 270 fragments were unidentifiable.

Observations

Unfortunately, only a small percentage of the bones was preserved, and their deterioration over time due to various postmortem factors did not allow their extended study. Therefore, it was impossible to determine the cause of death. Based on the observation of the fairly well preserved mandible, it was determined that a considerable number of teeth - all the right molars -were lost while the person was still alive. As a result, the alveolar bone of the mandible became atrophied. Furthermore, all teeth revealed serious decay, as well as caries in the form of a cavity at the contact point between the left first molar and the second premolar. All these elements are evidence of poor oral hygiene and could imply that nourishment with incompletely processed food was responsible for the dental condition. The decay could also be related to an unknown repeated activity. Furthermore, it is important to note another pathological find, one probably connected to intense physical activity. Despite the fragmentary condition of the vertebral column, signs of a concavity were observed on the body of a thoracic vertebra. Schmorls nodes (see above) appear on the body of the vertebra, at the joint with the intervertebral disc. As noted earlier, the interpretation of this pathological condition is still being investigated, although many scholars relate it to a serious injury or intense physical activity.

In conclusion, our current evidence concerning the state of health, nutri- tion, and life factors in the 13th-14th centuries is very limited. The results of the examination of the three skeletons from Vasilitsi, therefore, despite the fragmentary condition of the bones, may be useful for future research efforts and serve as a basis for comparison with similar material from other sites.

Lilian Karali

University of Athens faculty of philosophy department of history and archaeology

1. See, e.g., Nichoria III, pp. 353- 434; Dimitrokallis 1990; Hodgetts and Lock 1996; Davis et al. 1997; Davis 1998; Bennet, Davis, and Zarinebaf- Shahr 2000; Davies 2004; Zarinebaf, Bennet, and Davis 2005; see also Sigalos 2004, pp. 113-114.

2. Marios Michailidis executed the church's plans and reconstruction, while Ioannis Papamikroulis, architect, and Ioannis Haritos, topographer, produced the original drawings. Alan Stahl and Julian Baker identified the coins of the torneselli hoard, while Stavroula Doubogianni, Thanos Katakos, and Giorgos Tsairis were responsible for the conservation of the finds. Marina Georgoutsou produced the profile drawings of the ceramic vessels, and Giorgos Maravelias the photographs. Final changes on all artwork were executed by Irakleitos Antoniades, architect. Currently the finds are stored in the Archaeological Repository of Pylos (ARP), at the Fortress of Pylos, while the coins remain with the 26th Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities, Kalamata. Lilian Karali examined burials 1-3 in the Laboratory of Environmental Archaeology, Department of Archaeology and History of Art, University of Athens. Her osteological report, which appears as an appendix to this article, was carried out in cooperation with Ismini Kavoura and Daisuke Yamaguchi, both postgraduate students. Nia Giannakopoulos contributed to the palaeopathological stud

3. Selitza is a word of Slavic origin that signifies "village." The same placename is used for an area northeast of Kalamata.

4. The church is not found, e.g., in Sigalos s list of 10th-to 19th-century churches in Messenia (Sigalos 2004, appendix D, pp.234-236). I have been unable to determine from the local inhabitants whether the Virgins veneration is a survival from the medieval period or a later attribution to a preexisting building (cf. the case of the Panakton churches: Gerstel et al. 2003, p.174). In 2000, the residents of Vasilitsi, citing the religious significance of the church ruins, requested permission from the 5th Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities (then responsible for the area) to rebuild it. Since the building was previously recorded as a likely "early modern construction" (a "post-Byzantine double apse" church, according to the Ministry of Culture's archive), the Ephorate requested a thorough architectural study and restoration project. The residents submitted a proposal to reconstruct a new cross-in-square church. Fieldwork was undertaken in November- December 2000, both to assess the proposed reconstruction and to record surviving material that would date the building.

5. Both in the field notebooks and for the recording of finds in the Ephorate storerooms, the trenches were numbered following the Greek alphabet (A, B, T, A, E, It). Here I have adopted the Latin lettering A-F. The upper part of a large ashlar stone that had remained in situ and served as lintel of the passage between the naos and the narthex was used as the leveling point for all measurements

6. See Appendix, burial 2.

7. See Appendix, burial 1.

8. See Appendix, burial 3.

9. The tornesello is probably the most abundant medieval coinage found in the Peloponnese (for finds of torneselli, see Stahl 1985, pp.21-29; Davis et al. 1997, p.481; Gerstel et al. 2003, pp.227-228). It was a petty currency designed to facilitate everyday transactions (Stahl 1985, pp.7-10). Minted in Venice in huge quantities, it was then shipped to the Peloponnese, Euboia, and Crete to be used in the Venetian colonies. Torneselli rilled the gap left after the local Frankish mints ceased to produce deniers tournois in the first half of the 14th century. Production was initiated in 1353 and the coins circulated in the Peloponnese until the fall of Venetian rule in 1500.

10. In Corinth, for example, protomajolica wares comparable to 7-9 were imported only after the middle of the 13th century (Williams2003, pp.429-430), thus providing a terminus post quern for Vasilitsi.

11. In Messenia, e.g., see the Middle Byzantine chapel at Nichoria (Nichoria III, pp.370-371, figs.9, 10), Ayios Georgios at Vlachopoulo (11th century, Dimitrokallis 1990, p. 46), Taxiarchis at Polichni (10th century, Dimitrokallis 1990, p.78, fig.68), Panayia Grivitsiani (12th-13th century, Dimitrokallis 1990, p.101), and Metamorfosi Mesochoriou (13th century, Dimitrokallis 1990, p. 241).

12. Similar earth floors were found in the excavation of the Nichoria chapel, phase 4, ca. 1300 (Nichoria III, p. 372), as well as the Panakton village houses and central church narthex (Gerstel et al. 2003, pp. 154-155, 167, 169, 178).

13.Kupper l990,p.57.

14. E.g., Ayios Stefanos at Ramovouni (Dimitrokallis 1990, pp.57-69), Panayia Grivitsiani (late 12th-13th century, Dimitrokallis 1990, p.115), Ayios Vasileios, Petalidi (14th century, Dimitrokallis1990, p.203).

15. The same situation (foundation partly on bedrock and partly on soil) was observed in house 1 at Panakton (Gersteletal.2003,p.l57).

16. According to the standard typology of cross-vaulted churches established by Orlandos, it belongs to the T2 category (Orlandos 1935, pp. 49-50; see also Bouras 2001, pp.415-418). It belongs to the C2 category in Kuppers classification (1990, p.24, pl.3).

17. Kupper 1990, vol.2.

18. The date of these churches derives from dedicatory inscriptions, excavation data, or stylistic comparisons.

19. Soustal and Koder 1981, p.140; Doris 1983; Kupper 1990, vol. 2, p.160.

20. Evangelidis 1931, pp. 258-274; Soustal and Koder 1981, p.186; Kupper 1990, vol.2, p.150.

21. Bouras, Kaloyeropoulou, and Andreadi 1970, pp. 360-362; Ginis-Tsofopoulou 1982-1983, pp. 227-246; Kupper 1990, vol. 2, p. 126.

22. Dimitrokallis 1984; 1990, pp. 179-199.

23. As seems to have been the case for the Nichoria chapel (Nichoria III, p. 376).

24. Such as the deliberations of the Venetian Senate and Assemblies (Thiriet 1958-1961, 1966-1971), the documents relating to the Acciaiuoli estates in Messenia (Longnon and Topping 1969, pp. 19-130, docs. I-VI), the accounts of travelers, the Chronica byzantina breviora (Schreiner 1975- 1979), or the notary documents from Methoni and Koroni (Nanetti 1999).

25. The area has not been recorded in any of the surveys that were conducted in Messenia, e.g., McDonald and Rapp 1972, pp. 264-321; Nichoria I, pp. 108-112; Nichoria III, pp. 354- 356; Davis et al. 1997, pp. 477-481.

26. Panagiotopoulos 1985, pp. 263, 300.

27.Sigalos 2004 ,p.ll4.

28. Staboltzis 1976-1978, pp. 268- 270.

29. XpoviKov tov Mopecog,lines 1695-1710,trans. J.Schmitt, London1904, pp.116-117;Bon 1969,p. 61.

30. The Venetians are said to possess "the castle of Koroni with its villages and the land around it" (Gerstel 1998, p. 220).

31. See, e.g., Bon 1969, pp. 66-67.

32. Hodgetts and Lock 1996, pp. 77-78.

33. Bon 1969, pp. 263-264, 274- 275, 286-289, 291, 293; Panagiotopou- los 1985, p. 20, plan 2; Thiriet 1959, pp. 369-370; Gerstel 1998, p. 225.

34. For the presence of the monospito type in Messenia, see Sigalos 2004, pp. 118-131.

35. When M. Natan Valmin visited the area in the first half of the 20th century, he noticed ales mines d'un village appele Selitza, qui etait assez grand et qui possedait beaucoup d'eglises, dont on voit encore les restes. Le lieu sert aujourd'hui de refuge d'ete aux bergers des villages de Tinterieurn (Valmin 1930, p. 164).

36. Nichoria III, pp. 377, 423.

37. Longnon and Topping 1969, pp. 67-115; Gerstel 1998, pp. 228-233.

38. See Zarinebaf, Bennet, and Davis 2005, pp.151-209, esp. pp.174- 178. The cadastral survey (TT880) contains an astonishing amount of information that enables one to reconstruct a fairly accurate image of the area in question. The agricultural production consisted of vines, olive trees, cloth, and wheat, as well as livestock (sheep, goats, pigs), and bees; see Zarinebaf, Bennet, and Davis 2005, pp. 179-197.

39. Kupper 1990, vol. 1, pp. 90-120.

40. For the process that led from the extra muros Early Christian cemeteries to burials inside and around churches from the 7th century onward, see Tritsaroli 2006, pp. 25-28, 285-289; Voltiraki2006,p.ll50.

41. Tritsaroli 2006, p.40; similar stone-lined graves and simple interments were recorded in the Nichoria chapel {Nichoria III, pp. 372, 398-399) and at Corinth {Corinth XVI, pp.29-31, 126-128), Panakton (Gerstel et al. 2003, pp. 176, 196-214), Xironomi (Voltiraki 2006, p. 1151), and Thebes and Spata (Tritsaroli 2006, pp. 49, 176-177, 179).

42. See Tritsaroli 2006, p.28; Voltiraki 2006, pp. 1149-1150, 1152. Examples from the 13th-15th centuries come from the Frankish cemeteries at Corinth (Barnes 2003, pp.436-437), from Panakton (Gerstel et al. 2003, pp.197-198, 200-201, 206, 208, 210, 217-218), and from Thebes and Spata (Tritsaroli 2006, pp. 52-56, 60, 62-65, 162-163, 234-238).

43. E.g., at Corinth: Barnes 2003, p. 441.

44. See also Barnes 2003, p. 441; Gerstel et al. 2003, pp. 149, 215.

45.Stahll985,p.29.

46. Phenice 1967.

47. Brooks and Suchey 1990.

48. Bass 1971, pp. 212-213; Brothwell 1981, pp. 64-67.

49. Ortner 2003, pp. 363-370.

50. Aufderheide and Rodrigues-Martin 1998, pp. 400-415.

51. See, e.g., Aufderheide and Rodrigues-Martin 1998, pp. 96-110.

52. See n. 46, above.

53. See n. 47, above.

54. Bass 1971, pp.218-219; Brothwell 1981, pp. 51-54.