What the analysis of the early Mycenaean pottery can reveal

‘… only scattered sites have so far been discovered in Triphylia, despite much field work, and it is possible that the whole area between the Alpheios and the Neda (to the north of Kyparissia) was a no-man’s land, not strictly included in either the Elean or the Pylian kingdom.’1

Triphylia lies on the west coast of the Peloponnese between the rivers Neda in the south and the Alpheios in the north, which defined the region in historical times.2 Since Chadwick’s famous article on the Pylian provinces, archaeologists working in the area, notably fromthe Greek Archaeological Service, have made considerable progress helping to put Chadwick’s verdict into perspective.3 Current work on the site of Kakovatos and neighbouring Bronze Age settlements in Triphylia has been conducted by the Institute of Oriental and European Archaeology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in cooperation with the Greek Archaeological Service and adds to our knowledge of the region.

Due to the lack of administrative documents, the systematic study of archaeological remains forms the only source of information for understanding the Late Bronze Age (LBA) history of the region and its external relations. In this respect, the pottery from Kakovatos, Kleidi- Samikon, Epitalion/ Aghiorghitika and Lepreon/ Aghios Dimitrios (Fig.1) offers the opportunity to study the diachronic developments and regional as well as superregional relations of four different sites on a micro- regional level.

The sites

Kakovatos

Kakovatos (Fig.1.3) is themost prominent Late Helladic (LH) site in Triphylia and is especially wellknown for the richly furnished Early Mycenaean tombs (LHI late- LHII).4

The site lies on a hill around 2km east of the present-day shoreline and themodern village of Kakovatos. In 1907- 1908, W. Dörpfeld uncovered the three tholoi on the slope of the hill and the walls of a habitation site on the plateau.5 Further excavations under the direction of B. Eder and G. Hadzi- Spiliopoulou on the plateau took place in 2010- 2011 and uncovered remains of an architectural complex contemporaneous with the graves.

Typical domestic pottery categories, e.g. semi- coarse to coarse cooking/ storage pots and fine to semi- fine table wares, form the largest group of finds. Carbonized figs in a sufficient quantity associated with in situ pithoi, as well as spindle whorls and several spinning bowls, complement the assemblage that suggests a storage area, where foodstuff, implements for textile production and vessels for consuming food and beverages were kept. The excavators discovered a floor level, where debris, burnt and even vitrified vessels indicate the final destruction of the site in LHIIB.

This context illustrates that handmade Middle Helladic (MH) type vessels, mainly closed and rather large shapes, and Mycenaean pottery, mainly wheelfashioned and decorated drinking vessels, were contemporaneously in use.6

Kleidi- Samikon

The hills of Kleidi- Samikon (Fig.1.2) lie about 10km further north, near the coast at the west tip of the LapithosMountain range, where a settlement couldmonitor the paths along the coast from north to south (Fig.2).7 Archaeological activity started here at the beginning of the 20th century and established the existence of a Mycenaean habitation site on the largest northernmost hill8 and associated tombs in the surroundings.9

The most recent excavations were carried out by K. Nikolentzos and P. Moutzouridis in 2007 on the habitation site.10 In 2017, a geodetic and geoarchaeological survey was carried out in order to produce the first site plan and 3D model of the Kleidi hills with the location of the various tombs and structures.11

Due to erosion and intensive agricultural activities on the hill over the last century, the LBA settlement layers appear highly disturbed.Therefore, the evaluation of the pottery followsmainly stylistic and typological criteria. Despite these limitations, the pottery from Kleidi-Samikon offers essential information on the chronology of the habitation and the relations of the site with other regions of Mycenaean Greece.

At the present stage of research, the prehistoric settlement of Kleidi and the associated tombs seem to covermainly the LBA, although a small part of the pottery shows typical MH features in terms of fabric and shape (Fig.3. 1-2).12

The earliestMycenaean vessels from the settlement, e.g. shallow cups (FS218) with a framed spiral (FM 46) (Fig.3.4, 8), Keftiu cups13 (FS224) with a ripple pattern (FM78) (Fig.3.5) and Ephyraean goblets (Fig.3.6) date to LH IIA and LH IIB.14

The stipple pattern (FM77) on shallow cups (Fig.3.7) is typical for the LH IIB late- LH IIIA1 period, and its presence seems to indicate that the Kleidi settlement, in contrast to the neighbouring and prominent site of Kakovatos, remained in use throughout the transition from Early Mycenaean times to the palatial period.

Large amounts of pattern painted and plain kylikes (Fig.3. 9-10), as well as parts of kraters (Fig.3.11), represent the LHIIIA- LHIIIB pottery and are suggestive of festivities just as those that took place in other sites of the Mycenaean core regions.15

The LHIIIB2 material comprises a considerable number of deep bowls (Fig.3.12) and documents the latest phase of theMycenaean occupation on the Kleidi hill.16

By contrast, evidence for the post- palatial LHIIIC period is conspicuously absent. The decline or even the abandonment of sites in this period seems to be a widespread phenomenon in Mycenaean Greece, but this is particularly true for the south- west Peloponnese, where LHIIIC pottery is limited to very few sites in Messenia.17

Epitalion/ Aghiorghitika

Located on a ridge close to the mouth of the Alpheios River, the site controlled a strategic position on one of the few fords across the Alpheios and at a crossroads of routes to the north, south and east (Fig.4). On a clear day, one can see Kleidi- Samikon in the south and vice versa.

In 1967, P. Themelis excavated two rooms of a Mycenaean house, where large amounts of plain kylikes and parts of a bathtub stand out among his finds. Moreover, MH and Mycenaean surface finds are distributed across the hills.18 In terms of chronology, this site shows the same development as its neighbour to the south Kleidi-Samikon: vessels in the MH tradition are present (Fig.5. 1-2) as well as Early Mycenaean pottery, which was also introduced in LHIIA (Fig.5. 4-5). A large number of kylikes as well as other Mycenaean drinking and serving vessels (Fig.5.3,6-7) supplemented by painted and plain storage jars and cooking pots (Fig.5.8) represent the palatial period and indicate that, as for Kleidi-Samikon, LH IIIB2 was the latest phase of occupation.

Aghios Dimitrios/ Lepreon

The site of Aghios Dimitrios (Fig.1.4, Fig.6) lay close to the ancient polis of Lepreon, inland in south Triphylia and, unlike the previously mentioned sites, had no direct access to the sea. Indeed, it is mainly known for its Late Neolithic and especially Early Bronze Age occupation, but survey activities and the excavations in the late 1970s produced MH and LH material as well.19 Although the built remains of the Mycenaean period are not preserved, some stray pottery fragments indicate aMycenaean phase of the settlement.20

The majority of the 50 selected Mycenaean fine/semifine decorated and plain pottery sherds can be dated to the Early Mycenaean period, starting in LH IIA (Fig.7.1,3-4), although some LHIII sherds exist as well (Fig.7.2).

Triphylia as part of the Mycenaean core region

The analysis of the Early Mycenaean pottery fromTriphylia illustrates two important aspects. First, from a ceramicist’s point of view, Triphylia appears to have been less a peripheral area than a part of the Mycenaean core region from the very beginning. Second, this area was well- connected and part of Early Mycenaean regional and supra- regional networks.

Imports

Imports provide clear evidence for the existence of contacts with other regions. The examination of the material from the Kakovatos tholoi allowed identification of fragments of at least nine oval amphorae, a typical Minoan transport container.21 At the current stage of research, these tombs contain the highest concentration of this vessel type on themainland and it appears noticeable that this shape is especially common in Messenia.22 The petrographic, chemical and archaeological analysis of the amphorae from Kakovatos suggests that the majority were imported from Crete, but one also came from Kos in the Dodecanese.

A nearly complete Koan oval- mouthed amphora from tholos 2 at Myrsinochori- Routsi supports the idea that the social elite in Kakovatos acquired goods via the same interregional networks as the similarly elevated groups in Early Mycenaean Messenia.23

The oval- mouthed amphorae are just one category within a wide range of imported and precious goods from the tombs that indicate supra- regional relations.

The jewellery from the tombs, e.g. amber, gold and glass beads, forms another example for the extensive exchange networks that become visible in the burial gifts.The widespread contacts of Kakovatosmost likely affected the entire landscape and accelerated the spread and adoption of new ceramic traditions. As the most prominent site of Triphylia, Kakovatos probably promoted the integration of the whole region into the process of the emergence of Mycenaean culture.24

Furthermore, the petrographic analysis of the material, conducted by G. Kordatzaki (independent researcher/ research associate Fitch Laboratory, BSA) in collaboration with E. Kiriatzi (Fitch Laboratory, BSA), revealed that the inhabitants of LBA Kakovatos and Kleidi-Samikon had access to imports from Kythera. This island is well-known for industrial production of cooking pots and storage vessels in the characteristic reddish clay and rich in silver mica.25

The same characteristic redmicaceous fabric came to light in several sites, especially in Messenia and Laconia.26

The flat-based Minoan tripod cooking pot from the settlement of Kleidi-Samikon, petrographically assigned to the same fabric, serves as evidence for the introduction of Minoan cooking equipment. It thus seems likely that at Kleidi- Samikon, as in many other Mycenaean sites, together with the cooking pots a new exceptional cuisine was introduced and used to express social standing.27

While cooking traditions seem to have adopted some popular trends from Crete, the consumption of beverages and food followed other models.

The NAA results of H. Mommsen have shown that the settlements of Kleidi- Samikon, Epitalion- Aghiorghitika and Aghios Dimitrios had access to imports of fine Early Mycenaean tableware from the Argolid that complemented the locally produced pottery.28

Local production

Apart from imported goods, shared pottery styles and technical features indicate social relations and can even mark shared social practices. For example, the use of the very specific shape of the so- called spinning bowl with an internal basket handle suggests strong common traditions of textile production in Triphylia and the south- west Peloponnese, where the samples from Kakovatos find their only parallels.29

The distribution of LHI- LHIIA lustrous decorated vessels in the south- west Peloponnese points in the same direction. While in Messenia and Triphylia Mycenaean fine wares were already part of the local pottery production from an early point onwards, they do not seem to be present before LHIIB in the adjacent region north of the Alpheios River. Presumably, this pattern is significant for the existence and identification of zones of cultural contact.30

Certain ceramic features of Triphylian Mycenaean pottery give the same impression: typical LHIIA shallow cups (FS 218) with a monochrome interior came to light in Kakovatos,31 Kleidi-Samikon and Epitalion (Figs 3. 8, 5. 5). Themonochrome interior is known to be a feature ofMinoan derivation32 and otherwise only appears on shallow cups in Messenian contexts such as in Volimidia and Pylos.33 Furthermore, the distribution of motifs on the Keftiu cup Type III (FS 224) after Coldstream34 is also quite significant (Figs 3. 5, 5. 4,7. 4). 75% of the fragments of the Keftiu cups from Kleidi- Samikon feature the ripple pattern (FM78). The predilection for this motif has been observed for sites in Messenia35 and Laconia,36 while in the Argolid37 spirals were apparently preferred, and the Corinthia38 favoured floral motifs on this specific shape.39 These regionalisms underline once again the general impression that Messenia and Triphylia shared common aspects of their material culture in the Early LBA.

Therefore, the development of Early Mycenaean pottery of Triphylia blended influences from Messenia and the Argolid.

However, other elements point to the north Peloponnese and Central Greece. ‘Wishbone handles’, characterized by extensions reminiscent of rudimentary horns on their upper end, occur in Kleidi- Samikon (Fig.3.2) as well as in Epitalion (Fig.5.2) and illustrate relations with the north Peloponnese (Fig.8, Tab. 1), where similar examples are known from Mygdalia,40 Pagona41 and Aigion42 in Achaia.

Furthermore, this type of ‘wishbone handle’ appears in the Ionian Islands, Central Greece, Aetolia and Boeotia at the beginning of the LBA. Thessalian and Macedonian potters produced vessels with similar handle types from the end of the Early Helladic period until the LBA.

Another feature in the material of Kleidi- Samikon also indicates connections with the north Peloponnese and Central Greece. A fragment of an open vessel with a fringed scroll decoration (Fig.3.13) finds mattpainted parallels at Korakou in the Corinthia43 and Krisa in Phocis.44 Fringed geometric motifs seem to represent a typical element of the Matt-Painted tradition of Central Greece,45 but two LHII alabastra from Chalkis46 on Euboea and Tsiambaslar/ Chabaslar47 in Thessaly illustrate that curved fringed elements were adopted in Mycenaean lustrous painted pottery aswell.

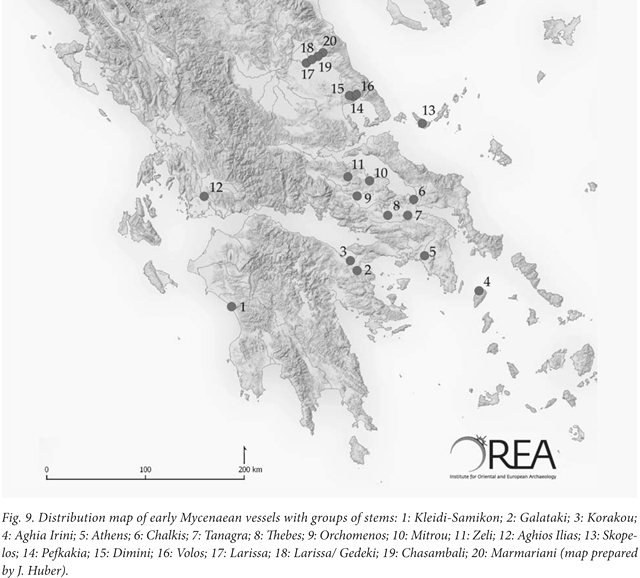

A specific Mycenaeanmotif consisting of groups of vertical stems on a shallow cup (FS218/ 219) from Kleidi-Samikon (Fig.3.3) is most common in the Corinthia, for example in Korakou, where this motif appearsmainly on cups and jugswith cutaway necks.48

Other instances are known from Attica, the Cyclades, Boeotia, Euboea, Aitolo- Acarnania, Central Greece and Thessaly. The groups- of- vertical- stems motif is mainly restricted to the north Peloponnese and regions further north and seems to be almost absent in the south Peloponnese (Fig.9, Tab.2).

Conclusion

Summing up, Early Mycenaean Triphylia does not convey the impression of a no- man’s land. Besides the richly furnished tholos tombs of Kakovatos that witnessed the rise and fall of an elite group, even the pottery of the lesser- known Triphylian settlements corresponds to the characteristic features of Early Mycenaean sites. The simultaneous presence of painted as well as unpainted Mycenaean pottery seems to prove the case. Its early appearance is related to the participation of Triphylia in supra- regional networks.

The connections with the south Peloponnese, especially Messenia and indirectly with Crete are mirrored in the predilection for specific motifs, shapes and modes of decoration as well as in imported vessels.

However, the material of Kleidi- Samikon suggests that Triphylia apparently lay at the interface of culturally different regions.

In this context, it also seems necessary to point out differences within Triphylia. In contrast to Kleidi- Samikon and Epitalion, Kakovatos lacks features like 'wishbone handles', curved fringed motifs or groups of vertical stems, which originate in the north Peloponnese and further north. However, a large amount of Cretan and other Aegean imports at this elite site indicates substantial southern connections, and at the current stage of research, it is also the only known site in Triphylia that has produced Messenian- type spinning bowls.

One possible reason for these differences could lie in the prominent hierarchical position of Kakovatos that presumably brought about a stronger connection with the south network, while in the other places influences from the north also become visible. While the most valuable products ended up in Kakovatos, the links to the south exercised an impact on the entire Triphylian region that was becoming Mycenaean.

Triphylia: A Mycenaean Periphery? What he analysis of the early Mycenaean pottery can reveal.

Η Περιφέρεια του Μυκηναϊκού κόσμου. Πρόσφατα ευρήματα και πορίσματα της έρευνας

Γ Διεθνές διεπιστημονικό συμπόσιο. Λαμία 2018

Περίληψη

Τριφυλία, Μια Μυκηναϊκή περιφέρεια; Τι μπορεί να αποκαλύψει η ανάλυση της πρώιμης Μυκηναϊκής κεραμικής

H Tριφυλία της Ύστερης εποχής του Χαλκού έγινε γνωστή κατά τις τελευταίες δεκαετίες, ενώ η μέχρι τώρα έρευνα επικεντρώνεται κυρίως στη μελέτη των ταφικών συνόλων. η μελέτη της κεραμικής του Κακόβατου καθώς και τριών άλλων οικισμών της Τριφυλίας (Κλειδί- Σαμικού, Επιτάλιο- Αγιωργίτικα, Άγιος Δημήτριος/ Λέπρεο) δείχνουν ότι η περιοχή μεταξύ του Αλφειού και της Νέδας ήταν στενά συνδεδεμένη και αποτελούσε τμήμα της Μυκηναϊκής κοινής ήδη από τις πρωιμότερες φάσεις. ειδικά κατά την πρώιμη Μυκηναϊκή περίοδο, η περιοχή παρουσιάζει πολλά κοινά χαρακτηριστικά, ως προς τον υλικό πολιτισμό, με τη γειτονική νότια Μεσσηνία, αλλά και εμφανείς σχέσεις με τη βόρεια Πελοπόννησο και με πιο βόρειες ακόμη περιοχές. στο παρόν άρθρο παρουσιάζεται η Τριφυλία ως τμήμα του κέντρου του Μυκηναϊκού κόσμου, καθώς και οι σχέσεις της με τις γειτονικές περιοχές στην αρχή της Ύστερης εποχής του Χαλκού.

* I wish to thank Kostas Nikolentzos and Panagiotis Moutzouridis for offeringme the opportunity to study the pottery from Kleidi-Samikon and Epitalion/Aghiorghitika for my PhD project, which is dedicated to the study of production, distribution and consumption patterns of LBA pottery in Triphylia.

I amalso grateful to Birgitta Eder for her support and academic advice within the Kakovatos project. Research has been carried out as part of the research project ‘Kakovatos and Triphylia in the 2nd millennium BC’ that is funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF project 27568) and the Institute of Aegean Prehistory. I also express my gratitude to the Hellenic Ministry of Greek Culture and Sports, the National Museum of Athens and E.-I. Kolia, director of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Ilia, for the permission to study the LBA pottery from Kakovatos, Kleidi-Samikon, Epitalion/ Aghiorghitika and Lepreon/Aghios Dimitrios and their ongoing support for our project. In addition, I wish to thank E. Kiriatzi and G. Kordatzaki (Fitch Laboratory of the British School in Athens) for the good cooperation throughout the petrographic study of the LBA pottery from Triphylia. My thanks go also to the organisers of the conference for the opportunity to present the preliminary results of my current work.

1. CHADWICK 1963, 136.

2. For an overview of Triphylia in the Classical and Hellenistic periods, see NIELSEN 1997; NIELSEN 2004; ROHN, HEIDEN 2009; HEIDEN, ROHN 2015.

3. ΝικολεΝτζοσ 2011.

4. DöRPFELD 1908a; MüLLER 1909. C. de Vree has fully documented all grave offerings and is preparing the evaluation of the finds in the context of contemporary tomb assemblages (DE VREE, forthcoming). For the petrographic and chemical analysis of the Palatial jars from the tholoi see HuBER et al., forthcoming.

5. DöRPFELD 1907, VI-XVI; DöRPFELD 1908a; MüLLER 1909; DöRPFELD 1913, 129-131.

6. EDER 2011a; EDER 2012; Χατζη-σπηλιοπουλου 2016a; 2016b; EDER et al. forthcoming. HuBER et al. forthcoming.

7. The strategic significance of this position continued to play a role throughout the centuries, resulting in the foundation of ancient Samikon on thewest end of the Lapithosmountain in the 4th century B.C.: ROHN,HEIDEN 2009, 356;HEIDEN, ROHN 2015, 334-335, 340; NIKOLENTzOS,MOuTzOuRIDIS forthcoming.

8. DöRPFELD 1908b.

9. Γιαλουρησ 1966; παπακωΝσταΝτιΝου 1988; 1989a; 1989b.

10. NIKOLENTzOS, MOuTzOuRIDIS forthcoming.

11. See EDER et al. forthcoming.

12. Due to the lack of stratified contexts, it proves to be challenging to decide if all these sherds represent actualMHmaterial or rather should be classified as part of anMH pottery tradition that continued during the Early Mycenaean period, as is the case with Kakovatos.Merely two almost complete kantharoi and very few fragments find their best parallels in pure MH contexts.

13. In accordance with F. Schachermeyer, I refer to FS 224 as a ‘Kethiu cup’ rather than as a ‘Vapheio cup’: SCHACHERMEyER 1976, 222-223. See also LOLOS 1987, 230-232.

14. EDER et al. forthcoming.

15. For the significance of plain and painted pottery for feasting, see BENDALL 2004; DABNEy et al. 2004; HRuBy 2006; JuNG 2006; VITALE 2008.

16. EDER et al. forthcoming.

17. Messenia in LH IIIC: MCDONALD, HOPE SIMPSON 1972, 142- 143; DAVIS et al. 1997, 451-453; EDER 1998, 141-178; 2009.

18. THEMELIS 1968.

19. zACHOS 2008.

20. MCDONALD, HOPE SIMPSON 1961, 232; zACHOS 1984, 328- 329, pl. 36 below; zACHOS 2008, 155 fig. 69.

21. MüLLER 1909, 323, pl. 24. Two restored amphorae come from tholos B andMüllermentions that in tholos A a high number of sherds of the same vessel type was found. See also DE VREE forthcoming. HuBER et al. forthcoming.

22. See e.g. Peristeria, tholos 3: Μαρινατοσ 1967, 117; Αντωνίου 2009, 711-712 no. 112, 114, 956-958 figs 164, 166-167. Myrsinochori-Routsi, tholos 2 (five amphorae): Κορρεσ 1978, 281-282, pls 182ε, 183α, β; LOLOS 1987, 210 figs 408, 409; αΝτωΝIου 2009, 726-730 nos 140-142, 145, 148, 1003-1007 figs 256-260, 1010-1011 figs 264-265, 1016-1017 figs 274-275. Koukounara-Gouvalari,tholos 2: LOLOS 1987, 170; Αντωνίου 2009, 708 no. 104, 950-951 figs 154-157. Koryphasion, tholos: BLEGEN 1954, 161, pl. 38a; Αντωνίου 2009, 934-935 figs 129-131.

23. DAVIS 2015.

24. EDER 2011b, 107-110; DE VREE forthcoming.

25. The macroscopic analysis of a body fragment found in the framework of the survey project ‘e multi-dimensional space of Olympia (Greece)’ suggests the presence of the red micaceous fabric in Epitalion as well. I would like to thank B. Eder and F. Lang for this information and the opportunity to examine the sherd.

26. KIRIATZI 2003, 125-127; 2010.

27. It is only since the last two decades that scholars have studied the significance of cooking vessels for several social, economic and political phenomena. See recently HRuBy, TRuSTy 2017.

28. The results of the archaeometric analysis of the pottery will be published in a joint article by the author with G. Kordatzaki, E. Kiriatzi, H. Mommsen and B. Eder.

29. EDER et al. forthcoming. For spinning bowls in Messenia, see LOLOS 1987, 338; zAVADIL 2013, 199-201.

30. EDER 2011b, 106-107; Nικολετζοσ 2011, 334-336. HuBER et al. forthcoming.

31. HuBER et al. forthcoming.

32. MOuNTJOy 1990, 249-251; 1999, 323; RuTTER 2003, 200.

33. Volimidia-Kephalovryson (tomb B): Καράγιωργα 1976, pl. 194γ; LOLOS 1987, 207 fig. 384;Mountjoy 1999, 323 no. 187. Pylos: BLEGEN et al. 1973, fig. 249 no. 27; MOuNTJOy 1999, 323 fig. 108 no. 22.

34. COLDSTREAM, HuXLEy 1972, 284-285; COLDSTREAM 1978, 393-396.

35. LOLOS 1987, 429; DICKINSON 1992, 481.

36. Menelaion: CATLING 2009, 341.

37. Mountjoy 1999, 70, 95.

38. Korakou: DICKINSON 1972, 105-106. Tsoungiza: RuTTER 1993, 79.

39. As amatter of course, Keftiu cups with spiral decoration appear in Triphylia as well, and so does this shape with ripple pattern in the Argolid and the Corinthia, but in this specific case the ratio between the different motifs is especially meaningful.

40. PAPAzOGLOu-MANIOuDAKI 2015, 315.

41. DIETz, STAVROPOuLOu-GATSI 2010, 124-125; STAVROPOuLOu- GATSI, KARAGEORGHIS 2003, 98-104.

42. PAPAzOGLOu-MANIOuDAKI 2010, 137, 141 fig. 17.

43. DAVIS 1979, 244 fig. 6 no. 69.

44. DAKORONIA 2010, 576; PAVuC 2012, 54.

45. VAN EFFENTERRE, JANNORAy 1938, 122 fig. 13 no. 18; DOR et al. 1960, pl. 32e.

46. Chalkis,Vromousa, TombIII:HANKEy 1952,66, pl.16 no.427; MOuNTJOy 1999,699 fig.286 no.13.

47. HUNTER 1953, pl. 22 no. A74; MOuNTJOy 1999, 830 fig. 332 no. 19.

48. Mountjoy 1999, 204.